Taxon Attribute Profiles

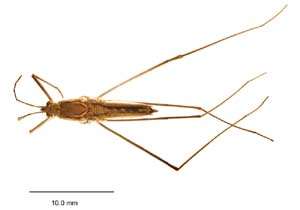

Aquarius antigone female

|

Aquarius antigone (Kirkaldy)

Water strider, pond skater

Introduction

Water striders or pond skaters are fascinating creatures which seem to

glide over the surface of the water. The pressure of a leg produces a

trough shaped depression (meniscus) on the water surface film, and the

surface tension of the water easily supports the weight of the insect.

Locomotion can be achieved through processes of walking, rowing, and skating,

and they can move quite quickly to catch prey or escape predation. Pond

skaters are predatory, and sense their prey by detecting surface ripples.

Taxonomy and Ecology

Classification

Order Hemiptera

Infraorder Gerromorpha

Family Gerridae

Life Form

Water striders are quite easy to recognize, and there is nothing

that they could be confused with. They are elongate, with long legs, and

they skate across the surface of relatively still water. Their middle

and hind legs are at least 3 times as long as their fore legs. There are

several groups of water striders, but within the Murray Darling Basin

there is only the genus Aquarius that reaches the size of 10-14

mm in body length (longer including the legs). Further characteristics

and diagnostic characters are given by Andersen & Weir (2004).

There are two species of Aquarius in Australia, but only A.

antigone enters the Murray Darling Basin. Four other species of water

striders, occur in the Murray Darling Basin: Tenagogerris euphrosyne,

Rheumatometra dimorpha, R. pilarete, Rhagadotarsus anomalus. They

can all be recognized from A. antigone by their smaller size (all

less than 10mm).

Click to enlarge map

|

Distribution

Aquarius antigone is found in the coastal areas of Queensland,

large parts of New South Wales, ACT, Victoria, and eastern South Australia

(Andersen & Weir, 2004).

Habitat

Water striders occur in large to small groups on the surface of still

water (ponds, lakes) and near the calm edges of flowing water (rivers,

streams). Adults and nymphs both inhabit the same types of areas, and

they tend to avoid fast running water. Their ability to skate on the surface

comes from their tarsi (terminal leg segments) being clothed in fine hairs

which prevent the tarsi from getting wet.

Status in Community

Both adults and nymphs are predaceous. As prey items are generally

insects that fall onto the surface of the water, it may mean that A.

antigone may not have the same effect in controlling population levels

of their prey as some other predators, because they may be differentially

preying on old and/or weak individuals.

Reproduction and Establishment

Reproduction

Ripples on the water surface are important signals, and can be used for

tracking prey, as well as for communication within the species. In some

species of water striders, ripples are used for attracting mates; in others

males use them to defend their territory.

Dispersability

Winged adults are rare in A. antigone, and one can expect very

limited dispersal between drainage systems. Thus, this species will be

more at risk due to local disturbances and changes in water regimes because

there is a low chance of recolonization from neighbouring regions.

Juvenile period

Eggs are laid either on floating debris, or sometimes underwater.

The nymphal stages do not differ significantly in morphology from the

adult stages. All stages are predatory, and they pierce their prey with

elongate beaks which they use to suck out the bodily fluids.

Hydrology and Salinity

Salinity Tolerance

Data concerning the sensitivity of Aquarius species to increased

salinity levels of other forms of environmental changes is not available.

In general, Gerridae have been seen to be moderately tolerant to salinity

levels (Gooderham & Tsyrlin, 2002; Chessman, 2003).

Flooding Regimes

Because A. antigone rarely produces winged adults, its ability

to respond to periods of flooding and drought is diminished, and its chances

for survival in areas which are intermittently riparian is reduced.

Conservation Status

Goonan et al. (2004) listed this species as rare for the Murray

River. It is actually quite common and widespread throughout eastern Australia;

however, it reaches the southernmost ranges of its distribution in the

Murray Darling Basin (Andersen & Weir, 2004). For this reason, it

might be locally rare, and more susceptible to environmental changes.

In other parts of the world Aquarius species have been shown

to be susceptible to environmental change. In Europe, A. najas

appears to be threatened due to a reduction in suitable habitats; and

A. paludum has increased its population levels conspicuously in

response to the creation of ponds stocked for angling (Nieser & Wascher,

1986; Damgaard & Andersen, 1996; Andersen & Weir, 2004). The effects

on other macroinvertebrates from the increased populations of A. paludum

have not been quantified.

Summary

A. antigone shares the characteristics of macroinvertebrates

that could make them suitable species for including in programs for monitoring

water quality (Water and Rivers Commission, 1996; Chessman, 2003; Minnesota

Pollution Control Agency, 2004), and European species of Aquarius

have shown that they respond to environmental disturbance and changes

in water regimes. These factors, coupled with the fact that A. antigone

can be easily recognized by non-specialists, and can be seen on the surface

of the water, makes them an attractive element for a program of monitoring

macroinvertebrates.

References

Andersen, N.M. & Weir, T.A. (2004) Australian Water Bugs: Their

Biology and Identification. Entomonograph Volume 14. Apollo Books.

Chessman, B. (2003) SIGNAL 2 - A Scoring System for Macroinvertebrate

('Water Bugs') in Australian Rivers, Monitoring River Heath Initiative

Technical Report no 31, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

http://www.deh.gov.au/water/rivers/nrhp/signal/

Damgaard, J., & Andersen, N.M. (1996) Distribution, phenology,

and conservation status of the larger water striders in Denmark. Entomologiske

Meddelelser 64: 289-306.

Gooderham, J. & Tsyrlin, E. (2002) The Waterbug Book: a guide to

the freshwater macroinvertebrates of temperate Australia. CSIRO Publishing.

Goonan, P., Madden, C., McEvoy, P., Taylor, D. & Gray, B. (2004)

River Health in the River Murray Catchment. Department for Environment

and Heritage, Government of South Australia. http://www.environment.sa.gov.au/epa/pdfs/river_health_murray.pdf

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (2004). Wetlands: Monitoring Aquatic

Invertebrates. http://www.pca.state.mn.us/water/biomonitoring/bio-wetlands-invert.html

Nieser, N. & Wasscher, M. (1986) The status of the larger waterstriders

in the Netherlands (Heteroptera: Gerridae). Entomologische Berichten

(Amsterdam), 46: 68-76.

Water and Rivers Commission (1996). Macroinvertebrates & Water

Quality. Water Facts 2. http://www.wrc.wa.gov.au/public/waterfacts/2_macro/WF2.pdf

|